early years

Alex Murray graciously provided us with articles (some annotated) and photographs drawn from Armstrong News, The Amis Newsletter, The instrumentalist, The Music Journal and The Galpin Society Journal that covered the early development of the Murray Flute. This collection of articles and images, including those written by Walfrid Kujala and Philip Bate, has been scanned into a PDF and can be downloaded or viewed in entirety here.

Here, in his own words, is Alex’s rationale for the Murray flute and a synopsis of the ways it differs from the standard flute:

Open G#

- The duplicate g# hole was unnecessary.

- The spring of on open key is lighter than one required to hold the key closed.

- Top e is greatly improved when correctly vented with the a hole alone, and not the a and g# holes together as on the closed g#.

- One finger one key (pad) on g.

I consequently asked a flute repairer to alter my instrument to the open g# and after a few weeks practice I found the readjustment amply rewarded.”

Open D# foot and D crescent

“The assymetrical use of the little fingers, in particular the necessity for maintaining the right little finger down much of the time struck me as undesireable and I experimented with an open d# by turning the foot-joint until the d# hole was within reach of my little finger. I unhooked the spring and maintained the key open with an elastic band. The flute became a little unstable to balance but I solved this by sticking a wedge of cork on the body above the right thumb. (I no longer require this crutch, having learned to balance the instrument without it.) I felt that the action of the key was an improvement on the closed d#.

At that time I was fortunate in meeting Albert Cooper, on artist-flute-maker, formerly of Rudall Carte who had left them to begin making flutes on his own. He agreed to construct a new foot joint which would convert my flute to open d#.

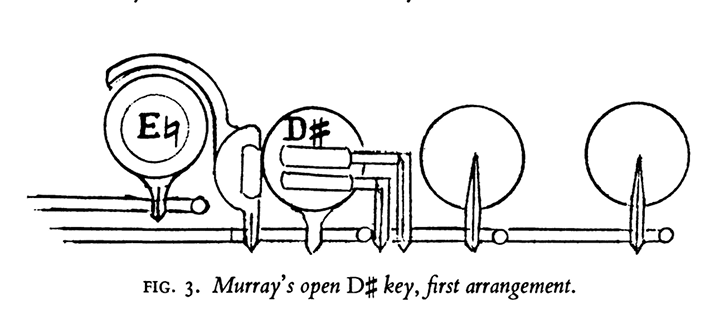

The c#, d, and d# holes were placed in line from an axle on the near-side of the flute; the d# key was closed by both of the other keys. The problem remained, how to trill c-d or c#-d. When the little finger was removed from c or c#, d# was the note thot sounded. In order to circumvent this, a crescent-shaped key was buiIt from the d key around the front of the ring-finger key. (I still use this mechanism on the piccolo.) This finger could then close both keys simultaneously when required, giving d#.

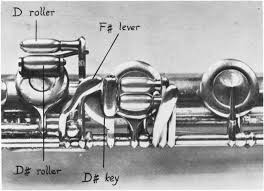

Later it was found better to have two parallel rollers so that the ring finger could move easily from d to d#, in the same way as the little finger moves from c to c# on a flute with two rollers on the foot- joint.”

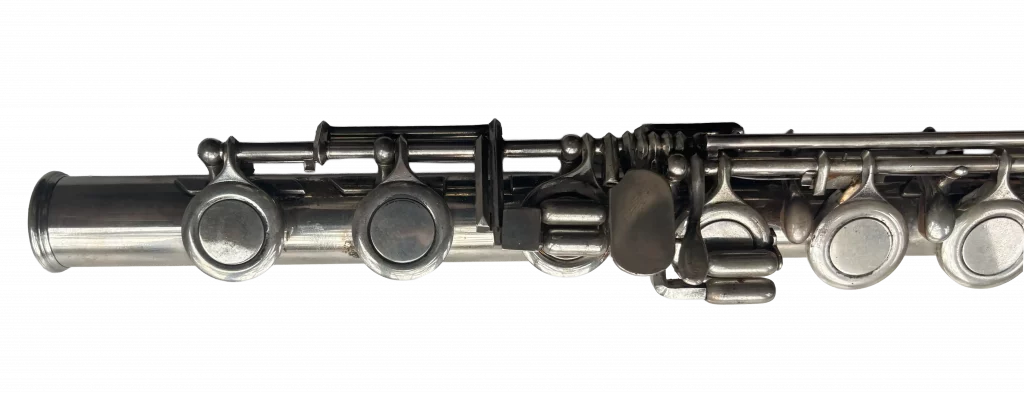

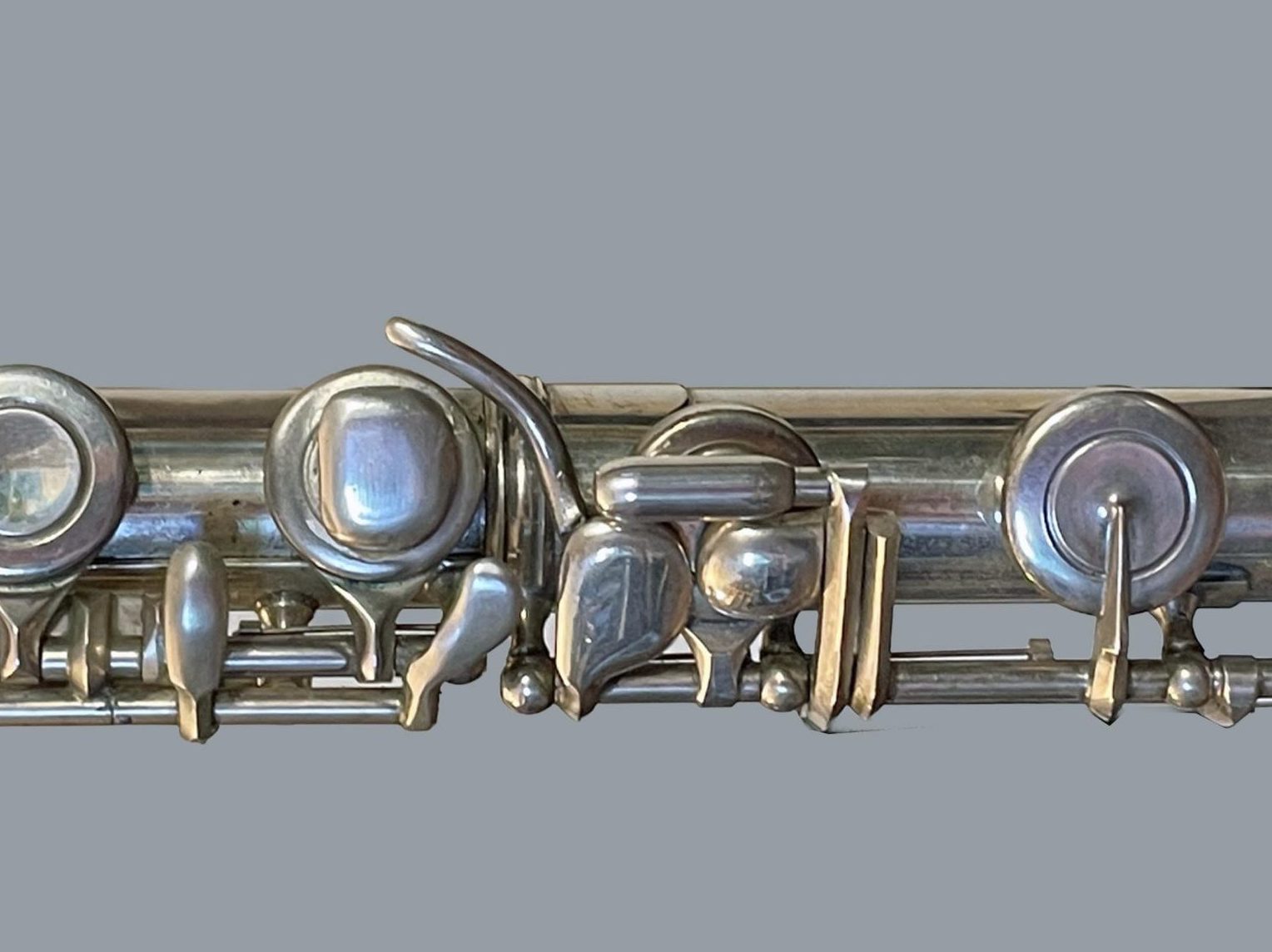

Foot joint detail from an early Albert Cooper Murray flute, courtesy of Leslie Timmons.

F# touch

“Once above d, the little finger is only required for d on octave higher. This led to the construction of a little finger key for f#, with several advantages. When f# is fingered in this way, alI holes below the f# hole ore open. A good trill for e-f# is provided with no change of fingering (for f#) and by splitting the a key (so that the b hole can remain open when the bb hole is closed) and connecting the lower key to the f# lever, the correct venting for top f# is mode practicable (comparable to top e on the open g#).”

Small C# hole

“The other notes which needed improvement were those using the small c# hole. The multiple functions of this hole are:

- a tone-hole for c#2 , 3, and 4

- a vent-hole for d2, 3, 4, d2 g#3 a3 bb

As Boehm pointed out, some compromise in its size and position is inevitable.

On many flutes the interval c#-d#2 requires careful blowing to produce a whole-tone acceptable to the ear (c#2 has to be flattened and d#2 sharpened, an unhappy juxtaposition of compensations). After several experiments a relatively simple mechanism was devised to divide the functions between two holes – a large c# tone hole and a small d vent. This entailed no change in the fingering apart from the reversal of the Briccialdi thumb keys and a return to the more rational order originally used by Boehm (b natural nearer the head joint).

The necessity in the top octave of putting down the right little ring finger for top b was obviated by linking the lower trill key to the d key. This automatically closes the d# hole when b is fingered normally. The effect on the trills is unnoticeable.

With these slight mechanical and fingering changes it has become possible to construct instruments with the hole placing correctly determined by the use of Boehm’s schema, without compensatory shifts of hole position to humor “bad” notes.”

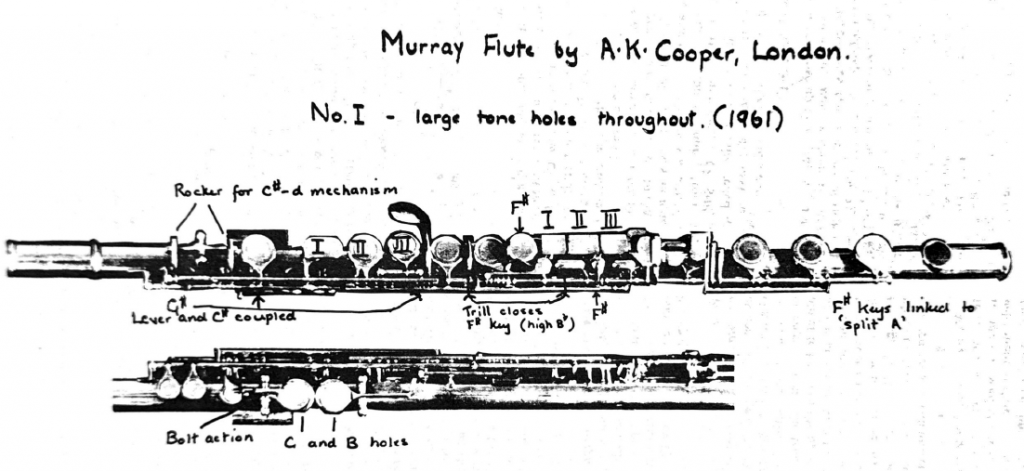

Albert Cooper & Jack Moore

“Without the skill, patience and insight of Albert Cooper, this flute would not be in existence. Inevitably he has been inundated with work and has a seven-year waiting list for his instruments. I have been most fortunate in meeting those responsible for manufacturing Armstrong flutes. The foreman, Jack Moore of the Heritage division, accepted the challenge of making a similar flute with certain slight mechanical improvements over my present one (my eighth) which I hope will embody the final form of the Murray flute. The following is on exact reproduction (in reduced form) of the Schema and fingering chart; also follows his data regarding the above story.”

(Please see Jack Moore’s schematics and notes in the PDF file here, pp 4-5.)

By 1974, Jack Moore had already made more than 50 Murray flutes. Alex and Jack first met after Alex reached out to Armstrong in the interest of having a student line Murray flute manufactured. Alex convinced Armstrong to send Jack to study with Albert Cooper In England, which no doubt helped make Jack the master craftsman that he was.

Murray adds in his notes, “Jack Moore has been responsible for many major and minor improvements to date. He produced two prototype flutes (the second of these was played at the Amis Convention in Washington, April 15-16, 1972 -ed.), fifty school model instruments, many with slight modifications, a Heritage silver flute, shown at the Amis convention Spring 1974, and is currently making a white gold model for the August National Flute Association Meeting.”

Student model Armstrong Murray flute, courtesy of Pat Zuber

Professional Armstrong Heritage Murray flute, courtesy of Leslie Timmons

Perhaps it goes without saying there were many more modifications to come in the ensuing years. Tom Green, who worked with Jack Moore, recalls:

“Alex would send Jack diagrams on his vision for a flute that he thought would improve the traditional fingering. Oftentimes Jack would have to call Alex to explain what he was trying to accomplish. It is one thing to draw something out and another to be able to integrate it into a workable mechanism. Our biggest joke was that Alex would write, “This is the last change.” We would say, yeah, right, and laugh.”

The Murray-Moore mechanism has seen dozens of iterations over more than 50 years of development, influenced by physicists and mathematicians including Arthur Benade, Elmer Cole and Ronald M. Lasewski, as well as the craftsmen who made the flutes.

In addition to Jack Moore, other fine flute craftsmen who made Murray flutes included Tom Green (who had access to a machine shop and made tools and mandrels for Jack Moore as well as assisting him); David Wimberley; the Brannen workshop; Keefe (currently making a Murray piccolo); and most recently, Juan Arista, who made a Lasewski scale headjoint in 2025 (and currently has the mandrel).

In addition to the very early Murray prototypes made by Armstrong intended for students a Murray piccolo was made as well. Murray alto and bass flutes were made by Emerson, and an experimental quarter-tone Murray flute was made by Kingma. There’s also a Murray flute resulting from a collaboration between Jack Moore and Robert Dick (see Gallery) that has an open holed thumb B flat. Jack Moore, who died in 2018, and Tom Green, now retired and in his 80s, are the only craftsmen to have made Cooper scale, Coltman scale and Lasewski scale Murray flutes.

We have been in touch with Jack Moore’s widow, Marilyn, and will soon have a database of all the flutes Jack made, so stay tuned.

The Sound of a New Flute

You’re probably wondering by now what the Murray flute sounds like.

Below are a few of the many recordings featuring Alex Murray on flute with the London Symphony Orchestra, where he played Principal for 11 years, from mid 1955-1966. Pierre Monteux’s tenure as Principal Conductor of the LSO (1961–1964) and his earlier guest appearances produced some of the most celebrated recordings of the stereo era, primarily for the Decca, Philips, and RCA labels. A select few are featured below. The flute duet with Joan Sutherland on Lo! Hear the Gentle Lark is truly masterful, matching trills and vibrato to Sutherland’s huge voice.

In 1973, Alex Murray made the first solo recording of the Murray flute: The Bach Partita (Lute Suite) in C minor for flute and harpsichord coupled with a hitherto unrecorded Duo Concertante by Carl Czerny for flute and piano. The keyboard player was Martha Goldstein and the recording engineer Alan Goldstein, a Peabody graduate on flute. These recordings and many more of Alex Murray and Martha Goldstein are shared courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Czerny Duo Concertante

1.Allegro

2. Scherzo-Allegro Molto

3. Andantino Grazioso

JS Bach BWV 997 – Partita No. 2 in C minor

1. Prelude

2. Fuga

3. Sarabande

4. Gigue

1990s - 2004: The Finale and a new scale

In the models made before the 1988, Alex sought to make a flute with hole placings and dimensions pursuant to Boehm’s ideal schema and without the need for compensatory adjustments to humor “bad” notes. He often stated his goal was to make the flute Boehm dreamed of making.

The problem wasn’t Boehm’s scale, but rather, the change in the tuning standard. Boehm’s flute was made to play at A=435 Hz. When orchestras changed to A=440 Hz, (recommended in the 1930s and officially codified by ISO in 1955), headjoints were shortened and the scale suffered as a result.

In the 1990s, when Alex adopted the Lasewski scale for his flute, that rubric changed. Lasewski scale necessitated significant changes in the placement of the tone holes as well as a very specific head joint that was more tapered up top, akin to a baroque flute, and slightly longer as well.

Tom Green recalls: “I remember when I went to Jack’s shop and we both looked in amazement at the dimensions of the Lasewski scale… We could not believe it would play. Comparing the placement of the tone holes, it was quite different from regular flute scales. Alex said it was to be matched with the head taper.

I know that I went ahead and made the mandrels and I must have made the bodies for Jack. I am assuming that Jack did not make the tooling. The head mandrel was made at a machine shop my brother and I owned. It was made on a Okuma CNC machine…

Jack made many Murray flute keys by piecing parts together. I started making casting patterns to save time and for consistency.”

About Ron Lasewski

Ronald M. Lasewski was a mathematician/physicist, Baroque flute enthusiast, and longtime colleague and friend of Alex Murray during his time teaching at the University of Illinois, Urbana. Lasewski wanted to know what physical characteristics made his Baroque flutes sound the way they did. He studied their acoustic characteristics — especially, the distance between the first and second partials and the third and fourth partials of each note — and recorded corresponding physical measurements.

Over time, he programmed a computer to model what the acoustic result would be in pitch and timbre to any physical adjustment to hole size, placement, venting or bore dimensions. He made some thirty-odd Baroque flutes using his “Traverso” program, studying and learning from the results.

Now applied to Alex’s flute in C, the program’s ability to predict how one change to the flute could affect every note in the range took Alex light years ahead in his ability to experiment for optimal results. Even with the aid of Traverso, it still took 13 tries to make the Lasewski scale tapered head joint, according to Alex.

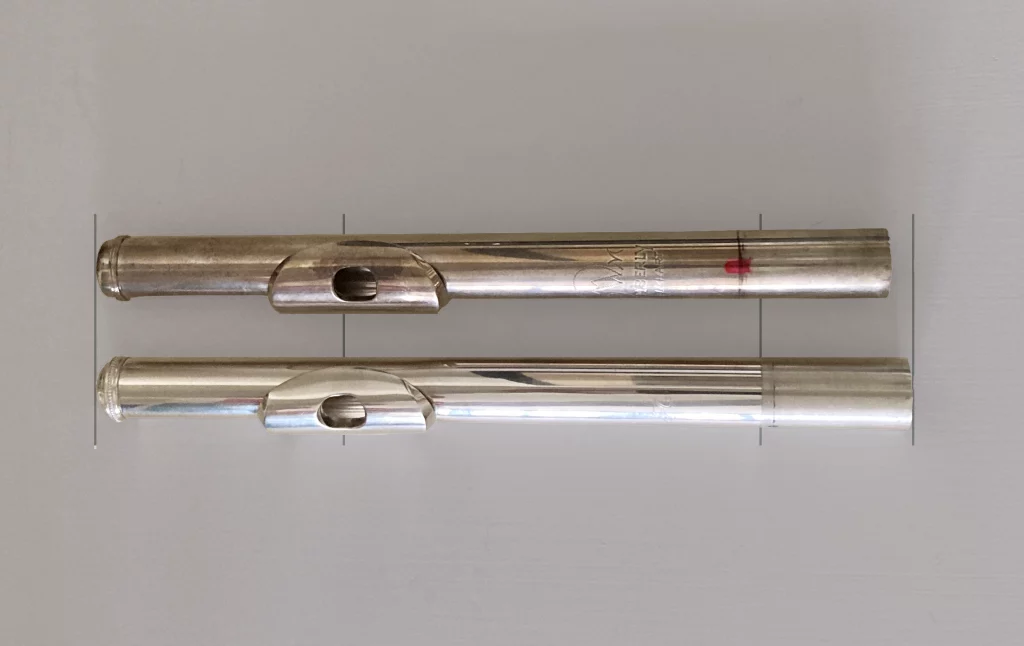

Top, Standard headjoint (David WImberly); Bottom, Lasewski scale Murray headjoint (Juan Arista)

Note how much narrower the Lasewski scale head is at the crown side; the distance to the center of the embouchure holes (placed standard distance from cork); and the length.There is a special mandrel used to create this headjoint, Juan Arista has it.

Below, the Lasewski scale prototype XV made by Jack Moore (top) and the XVI Tom Green made 4 years later, in 1998. For reasons as yet unknown, the 1998 XVI plays with a fuller low register.

Key Differences

If you try to play the Murray Lasewski scale flute with a standard flute head joint, it may fit into the body of the flute but it won’t work. The acoustic problems will manifest in the extremes of range, both low and high. (Juan Arista currently has the mandrel Tom Green made for the Lasewski scale headjoint).

This is entirely subjective, but having played Murray flutes with both scales, I note that you cannot push as much air through the Lasewski scale flute – but the good news is, you don’t need to! It’s an incredibly resonant instrument. Find the sweet spot and it almost plays itself. From a fingering standpoint, I did not notice the changes made to placement of the tone holes. There are a number of alternate fingerings specific to the Lasewski scale models that you can explore here.

The Lasewski scale models add another important feature to the Murray-Moore flute: a half-hole mechanism that brings the top octave in tune. It can be switched on an off with a tiny lever.

These models go down to low C only and employ closed hole keys for acoustic reasons.

Until the very end, Alex continued to make small modifications to his mechanisms. In the last flute Alex had made in 2004, the body was merged with the foot joint and the D crescent was placed just atop the D# key cup (instead of around it) with a bit of felt in between and a slightly raised button of silver on the D# key cup, presumably to slide between D and D# with less movement of the ring finger. This raised button is also seen on the 1994 Lasewski scale prototype but it’s paired with the standard D crescent. The 1998 Tom Green Lasewski scale flute does not have Rockstro F# between E and D# or the raised button on the D# key and the D crescent is in its usual place, hugging the exterior of the D# key and adjustable by the player.

1998 Tom Green Lasewski scale XVI flute with half-hole mechanism in "on" position.

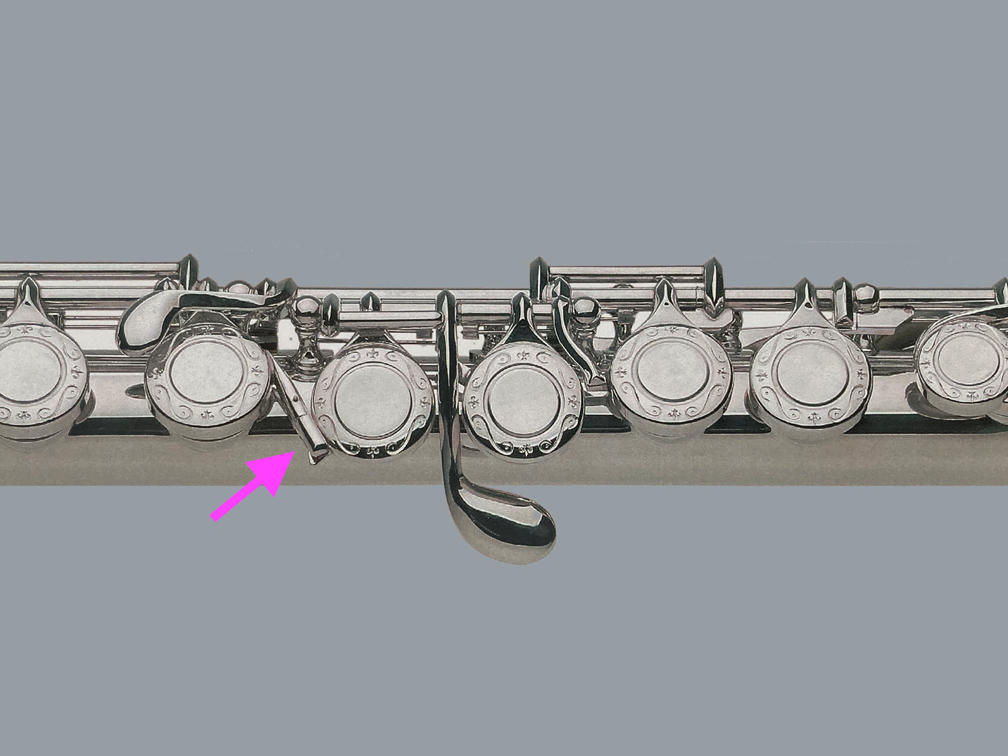

1994 Jack Moore Lasewski scale XV prototype with raised D# and a Rockstro F# key between E and D# cups (as on pre-Lasewski scale models).

1998 Tom Green flute with unraised D# key and D crescent, stacked Murray trills.

2004 Murray-Moore-Lasewski Finale with unibody, raised D#, overlapping D crescent and stacked Murray trills (not shown).